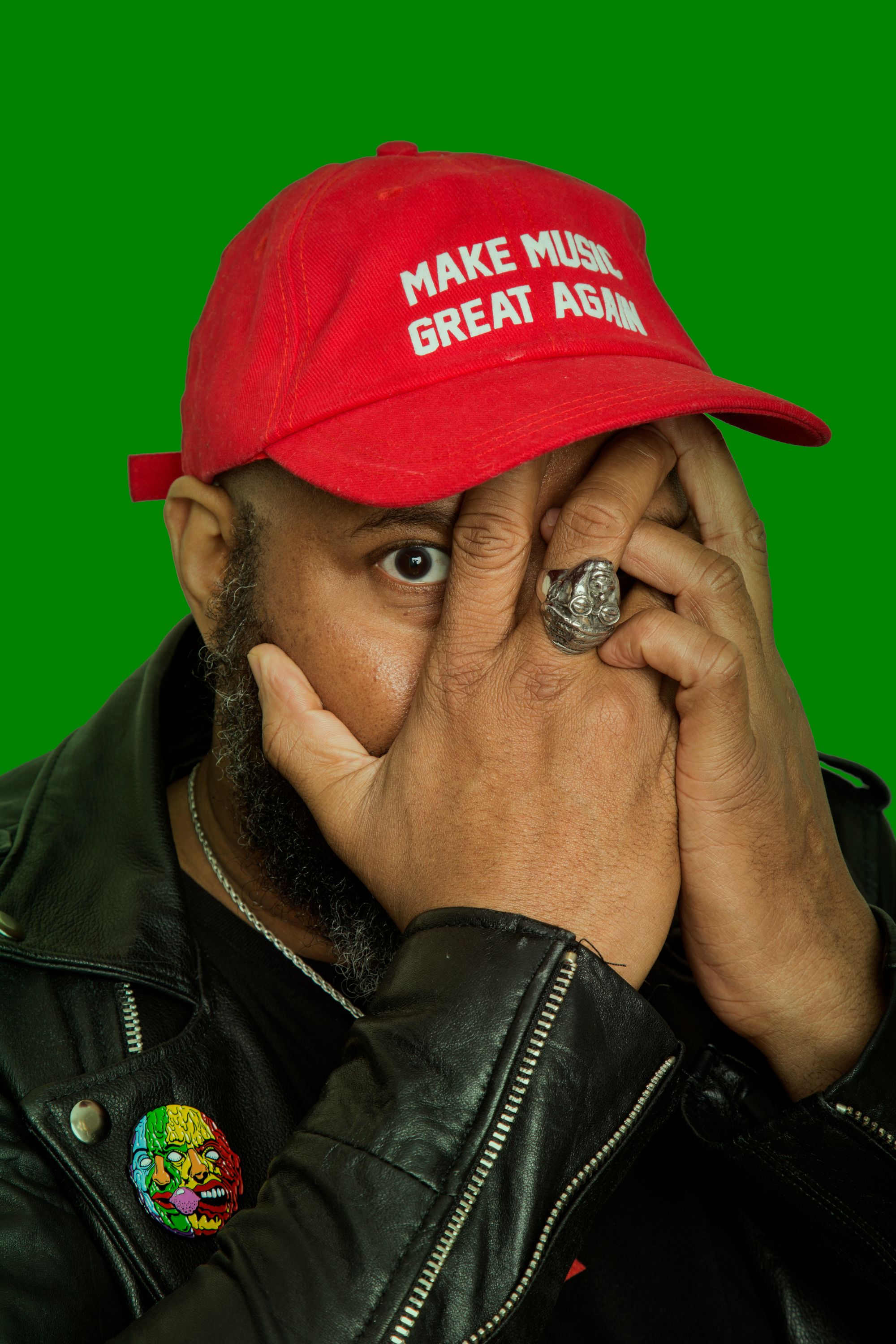

Beans: The Cabbages Interview

"Even after all these years, I still have something to prove."

One of the dopest emcees alive, Beans entered the hip-hop fray as part of the seminal NYC-underground group Antipop Consortium. When that pioneering project disbanded in the early 2000s (ultimately reuniting later that decade), he pivoted to a solo career, releasing provocative and experimental rap albums for labels like Anticon, Warp, and his own Tygr Rawwk Records. We recently sat down over Zoom to discuss his new single Bermuda Serpent Saliva Man, some notable moments in his multi-decade career, and his ever-evolving craft.

You've been on a roll since 2017, with these multiple projects on Tygr Rawwk like HAAST and Venga. And it came after a quieter period for you. What prompted this resurgence that's continued now well now into 2021?

Honestly, I took a five-year break–and I feel there's no time for breaks anymore. I mean, right now, I'm kind of in a rest period. I think this year it's just going to be singles, maybe two or three more singles, and then an EP that I have planned with Vladislav Delay.

It's funny you mention that. When I used to go into Other Music—and I know you're on that compilation—in 2001, 2002, I'd see your records there, the Antipop records, stuff by Vladislav Delay. Those were things that I would end up just picking up and buying.

I worked at Other Music during [the time of DJ Vadim's] The Isolationist. I quit maybe two months after Tragic Epilogue came out because of touring. I worked there for two or three years. That store was education. That store was New York. This was a time in New York that's very special to me, that whole period. [sighs] Damn, I miss that era, you know, just for the cultivation of the music alone. I got exposed to krautrock and a lot of electronic music at Other Music. I learned so much about music working there.

It was an education for the buyer as well. I would go in and there was so much discovery you could do. I was super intimidated by that place.

Everyone was.

I wouldn't speak to anybody who worked there. I always thought, these guys are fucking geniuses and I don't know shit. You guys who worked there, you had this reputation. We all thought you were made of stone and would cut us down if we asked a question.

[laughs] Nah. Some of us was like that. It all depended on the day. I was like that sometimes, but not really though. I met a lot of cool people working there who used to come in looking for stuff. But as I said, man, I got exposed to so much music working there, stuff I never even heard of before that now I couldn't live without. It was amazing. I don't know why they hired me, but I'm glad that they did.

I appreciate Other Music for introducing me to Muslimgauze. I liked his beat stuff. His approach to beats was kind of like, off. It was off, but it was on. And I liked the fact that you could rhyme to it, but it didn't necessarily need rhymes to it. I was like, wow, how come nobody's ever rhyming on Muslimgauze joints? These are beats that are straight up bangers. Nobody even really knew who he was. By the time I discovered him, I think he’d just died. And all that stuff was coming out. I’m guessing in terms of output, he’s close to Sun Ra.

You've got this hybrid of knowing and living hip-hop history, being from White Plains, from the seventies. I always thought I heard in your sound this understanding of everything from [Herbie Hancock’s] “Rockit,” the preceding stuff at the parties out in the parks, and then also fusion with stuff like Muslimgauze. By the time you were making [2004's] Shock City Maverick, were you thinking about these artists actively when creating or was it part of your process at that point?

You know what was big in my mind what making Shock City? Suicide. In terms of production, it was just like synth and drum machines. And a lot of early Mantronix too. Mantronix was big—and also Autechre. I mean, you can't really talk about Autechre without mentioning Mantronix. I also got into Tod Dockstader. Out of all the musique concrète stuff, his stuff was a little bit more—not beat heavy per se, but more progressive. More so than with Pierre Henry. I know that he was a big influence on Autechre as well. So I got exposed to them through that. And then Suicide was real. They have heavily influenced me, production-wise definitely.

The work you've been doing for Tygr Rawwk has largely been with other producers. What do you look towards these other people to bring? Are you looking for commonalities, like a shared ear?

I'm looking for variations that will still excite me enough to try and write to it, and how I can work within these variations. I'm looking to work with various people to do things that will be different for me. Working with Ay Fast on all these other records, sometimes it takes me a while to write to his beats. I find them kind of challenging and I don't always know how I'm going to write to them. And some people just came along the way. Ace Balthazar was with Ade Firth. I’d only did that track with him on [2011's] End It All, “Superstar Destroyer.” He reached out again and then that's how that came about.

It all goes back to that five-year period. I was doing work on the three albums initially, which was Wolves Of The World, Love Me Tonight, and HAAST. I was working on those and I was writing the book Die Tonight all at the same time. Honestly, I never really stopped working; I just was trying to work on all those things at once and it just took that long to do it. But within that time, I was still accumulating all the beats that you're hearing now. There's still five more joints that's gonna come out like this. I’ve planned five joints to come out next that you'll hear it within the next two or three years.

This burst is rewarding. because not only do we get new music, but also there's this reflection of your progression as an artist for those who remember your work from 2001, now hearing you 20 years later. Are you conscious of your growth and development as an emcee?

I feel, now that I'm older, I can take more risks. A lot of jazz cats, as they got older, they took more risks. I feel like I'm at that point. I could try more things. I'm not limited. I understand what it is that I'm doing, more so now, so I can develop more within that frame of what I started. I could branch out and expand more. As I'm getting older and more comfortable with myself, I can try to experiment in different ways and do different things. I feel a lot freer getting older, artistically. There are certain things that I want to do that I know I'm going to do that haven't been done yet. I just don't give a shit. [laughs]

I have a way that I hear music and I just want to just move forward and propel that. There’s no limits now. I'm really so comfortable in who I am right now. I’m glad that people are receptive to it. I'm really appreciative that people such as yourself have grown with me and seen the growth. There's still things that I want to do, things that I want to try, and things that I haven't done yet. I'm invigorated by the aspect of doing things that people haven't heard yet. That still really excites me. It motivates me to still want to do and try different things.

Now that we're in this environment where you can put material out in a short run or digitally, how are you adapting there? How do you feel about the way that the market has changed for music consumption, where you're able to put out a project and not necessarily have to engage with the wider industry?

Yo, it feels liberating. I could still do like two albums a year, or choose not to, or just singles. I don't think I would have had the same output if it was more of a traditional sense. But now I control the terms of how I put out music. No one's telling me what I can and can't say or do. I have total complete freedom in that regard now, in a system that works and benefits me doing that. So I'm thankful. And as a listener, I consume a lot more music now, based on the fact that other people are doing the same thing. I love listening to all the new stuff that's coming out now. But as an artist as well, it's completely liberating.

Bermuda Serpent Saliva Man is a standalone single. Why is that not the centerpiece of an album for you? What is it that makes you say, I want to do this as a two track single?

All right, well, I'm going to tell you. I put out eight albums in three years, something like that. I'm tired. Not literally. That’s it; I'm just tired. I need to recharge. I need to take a break. I didn't want to put not-anything out, but I wanted to slow it down a little bit, still be productive. I'm still planning. The next five is already scheduled. I know what I'm gonna do. I got to pump the brakes a little bit, catch my breath.

So looking back 10 years, 2011 was an interesting year for you and thus makes 2021 an interesting anniversary year for a couple of your releases, including End It All. How did you come first to kind of connect with those guys at Anticon?

From the outside looking in, I liked how they represented themselves over there, what they did and how they were doing it. I thought that it would be a nice fit for me at that time. I actually approached them, reached out and built a relationship with them slowly. Honestly, I wasn't gonna rhyme anymore; I was going to quit. That's really why I called it End It All, because that was supposed to be my last record. I was out after that. That was going to be it for me, but things didn't happen that way. [laughs]

Listening to it now, it seemed like you were ceding some control with that record. You had historically played such an integral and holistic part in the music you were making, on the mic and behind the boards even on collaborative projects.

Yeah, that was actually the last album I stopped producing for self.

How did you come to that decision?

The reason why I started working with other producers is because the feedback that I was getting from my solo production was that people weren't really feeling it. They didn't weren't really understanding the approach that I was trying to get at. And I realized that, as someone who was producing their own work, that I wasn't ever in love with the process of production. Production, for me, was a necessity that I had to do at the time, because of the fallout with Antipop. And it had to be in my own hands. I mean, it was something that I had an interest in. I had ideas and approaches that I wanted do, but I was never in love with production.

I think producers, or when you produce, you have to be in a specific mindstate to do it. You have to love doing it. You gotta love being crouched over. Some people like going and spending like three hours looking for the perfect kick, like, in these 50 records. Some people like that. I had to do it because it was a necessity, ‘cause I wasn't hearing music that I could rhyme on of what I was trying to say at the time. So it was something that I felt that I had to do, but, I was never really in love with production. When people weren't really feeling it and saying that I needed a producer or I needed to do this or the music wasn't this and it was a disconnect, I kinda bowed out gracefully.

I thought that, you know, there were a lot of people who were doing sort of what I was hearing, but they were doing it better. And I said, all right, well, if they're doing it a little better than maybe I could work with people who are doing it better. It actually makes it easier for me to just write to a track. I have some input, especially now, in how things sound when working with a producer like Ay Fast. We talk a lot. So even if he may present me with a track, it's always in the context of something that I'm looking for. We have that synergy. It’s been beneficial to both of us, but as I said, he still presents a lot of challenges. This stuff is not easy to write to.

I get it. You found the thing that you love to do and what part of this you didn't necessarily want to keep doing.

I’m definitely more comfortable conceptualizing and writing. I'm more comfortable with that aspect than I am, like, production.

I'd love to ask you about [2011’s] Knives From Heaven with pianist Matthew Shipp and bassist William Parker. I know you and Shipp had worked together before; there was the Antipop Vs Matthew Shipp record in 2003. And when you were doing your solo stuff, you worked with Parker on 2006’s Only. What brought you back to working again with them?

Priest. I think that was the record that we did before Fluorescent Black came out. It was going to be a little side thing. It was initially supposed to be the four of us [from Antipop], but it ended up just being Priest, myself and Earl [Blaize]. So it was kind of an Antipop thing again, a re-coalescence of Antipop, really.

The first one [Antipop Vs Matthew Shipp] doesn't really have a nice aftertaste, because we had just broken up. For me, it has a bad memory. We were fractured and we were leaving. There were certain tracks that I did, certain tracks that Priest did. We had did the initial recording together. It just represents a whole like breakup mode, how everything was like on the outs with Antipop. So the first one was rough.

Because you guys weren't talking at that point, by the time that record came out.

Nah. [In 2011,] it was good because it was still getting back together again at that time. It was still fresh. That album [Knives From Heaven] was more of a reacquaintance with each other, as well as with Matthew Shipp, doing that. A lot of that was written while we were touring, as Fluorescent Black was coming together? It was good to re-establish the working relationship between us again, in that regard. So it was good. I liked that record.

Full disclosure: the first time I heard Antipop Consortium, I didn't understand it. It's one of those things where over a period of time it starts to click. But the first time I heard “Ghostlawns,” I didn't understand it. Then when I got to “Mutescreamer” a couple years later, my brain was like, I get it now. This is a longwinded way of saying, it does require a certain amount of listener education to understand it.

Is that bad though? Should it be immediate like, I understand this, real quickly? Is that such a bad thing when it doesn’t?

When you're young, it's easy to compartmentalize. Like the way when you walk into a record store when you're 19. It’s organized in a certain way—the punk and hardcore records are here, the metal records are there, the jazz records are here. It often takes, I'd say, from a listening perspective, an artist who's willing to challenge a genre line to prod at those borders to make a listener go, oh, you know, maybe I should check it out. There's a difference that comes through that exposure to artists who are at the very least poking at the borders or moving across them or, in some cases, just demolishing them. I listened to both sides of this new single. And they are totally different. The B-side “Viragor” could be on the radio!

You know, I listen to Rome Streetz and I listen to Benny [The Butcher]. And I hear them say this thing in their records. I don't know who they’re talking about. They say this thing about rappitty rap. And I don't know. You hear him say that? I don't know who they're talking about, but there's some line in the sand that they have. I don't know where the line is, but I wanted to do something where it'd be like, all right, well, you may not like a certain type of hip-hop. But all I know, from my side of the fence, you can't say that I can't rhyme. You may say that I may have an ill eight minute thing and it may be all weird. But you can never tell me that I can't rhyme over a straight-ahead track.

So that's why I put the two together, ‘cause you're not going to expect those two together as one single. You hear the eight minute thing like, yo, what the fuck is this? And then you hear, yo, this is a straight banger, this dude could actually rhyme to a track. I didn't want no confusion. Like, don't ever say I can't rhyme. I can rhyme. I like to experiment. The whole mission for hip-hop is to experiment. I mean, it started from music that you got to plug into a lamppost. There's no straightforward thing about this. There's nothing straightforward about hip-hop at all. It should never be straightforward. There's no rules to this. Any parameters you put are the ones that you put on your own. You put me in front of a straight track. I will destroy it. And I had to make that distinction quite clear. Even after all these years, I still have something to prove. This is still emceeing, this is still bars.

Purchase Beans’ music, including the just-released Bermuda Serpent Saliva Man single, here.